By Carl Zebrowski

Germany was a military juggernaut in 1940. The United States was not. America had been victorious in its wars leading up to World War II, but now its military barely ranked in the world’s top 20. It had less than 200,000 men in uniform, and some of them were wearing doughboy helmets from World War I and carrying guns that dated back almost to the turn-of-the-century Spanish American War.

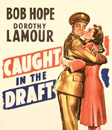

As it became clear that it was merely a matter of time, and not much of it, before the United States was forced to enter World War II, something had to change fast. Those “I Want You” posters with the finger-pointing Uncle Sam were pretty persuasive, but there was no way enough volunteers were going to enlist to build a military strong enough to challenge Germany and Japan. So in September 1940 Congress passed the Burke-Wadsworth Act to initiate a military draft, the first peacetime draft in American history. Young men ages 21 through 36 were required to register for the possibility of 12-month terms of service in the Western Hemisphere or in US territories or possessions. Some 20 million men had to register right away.

As it became clear that it was merely a matter of time, and not much of it, before the United States was forced to enter World War II, something had to change fast. Those “I Want You” posters with the finger-pointing Uncle Sam were pretty persuasive, but there was no way enough volunteers were going to enlist to build a military strong enough to challenge Germany and Japan. So in September 1940 Congress passed the Burke-Wadsworth Act to initiate a military draft, the first peacetime draft in American history. Young men ages 21 through 36 were required to register for the possibility of 12-month terms of service in the Western Hemisphere or in US territories or possessions. Some 20 million men had to register right away.

To process the registrations and administer the draft, local draft boards were set up from coast to coast. Each of the 6,443 boards assigned each of the registrants in its district a number, then a national lottery was held to rank the registrants. In Washington, papers with the numbers 1 through 7,836 printed on them were put into capsules, one number to a capsule. The capsules were dumped into a giant fishbowl that had been used for the same purpose in the WWI draft. The capsules were then stirred with a wooden spoon fashioned from part of a beam from Philadelphia’s Independence Hall. Finally the capsules were drawn from the bowl one by one to establish the draft order. In a predictable photo opportunity staged on lottery day, October 29, 1940, a blindfolded Secretary of War Henry Stimson reached into the bowl and pulled out the first capsule. From a nearby podium, President Franklin Roosevelt announced the number drawn: 158. Across the country, 6,175 young men held that number.

All the men holding number 158 were brought in first by their local draft boards to be considered for service. Men holding the numbers that followed in the lottery were brought in until the services had their fill. All the men whose numbers were up received an “order to report for induction” from their local draft board. The letter named the branch of service the man was being called to and gave the date, time, and place where paperwork would be filled out and examinations given. A man had to be at least five feet tall and no taller than six and a half, be at least 105 pounds, have vision correctable with glasses, have at least half his teeth, not have been convicted of a crime, and be able to read and write.

There were several reasons a man might be sent home. Men who didn’t pass the medical examination were classified 4-F, physically unfit for service. Black men were passed over initially due to prejudiced questions about their ability to fight and worries that tensions between black and white servicemen might erupt. Men in certain occupations deemed essential to the war effort were excused so they could continue to do their work. And men with friends on their local draft board sometimes slipped through cracks.

The inductees who passed all the scrutiny were taken into the service right away. As the induction letter for 1941 stated, “Bring with you sufficient clothing for three days.” It may have felt like being hauled off to jail without the opportunity for bail. The next stop was a stateside military installation and then, for most, shipping off to Europe, Africa, or the Pacific.

Drafting continued through the war, though a lot changed after that first round in 1940. Among the obvious changes were the expansion of the age range to include men from 18 to 37, the elimination of restrictions on where in the world a man could be sent, the growth of the enlistment term to the duration of the war plus six months, and a growing tendency to overlook physical shortcomings. By war’s end some 35 million men had registered and 10 million were drafted. The draft had produced a military that could not only stand up to Germany and Japan, but could decisively defeat them.

Copyright 310 Publishing, LLC. All rights reserved.

FOLLOW US »