Genius. Jerk. Call him what you will, General George Patton managed to do the impossible while alienating peers and subordinates alike.

By Richard Sassaman

“[Patton’s] nervous energy, his drive, his sense of history, his concentration on details while never losing sight of the larger picture combined to make him the preeminent American army commander of the war.”

—Citizen Soldiers: The U.S. Army from the Normandy Beaches to the Bulge to the Surrender of Germany (1997), Stephen Ambrose

“[Patton was] a swaggering bigmouth, a Fascist-minded aristocrat…brutal and hysterical, coarse and affected, violent and empty…quite mad.”

—Dwight MacDonald, America social critic quoted in The New York Review of Books, December 31, 1964

“Everything that everyone has ever said about George S. Patton, Jr., is probably true.”

—The Patton Papers (1972), Martin Blumenson

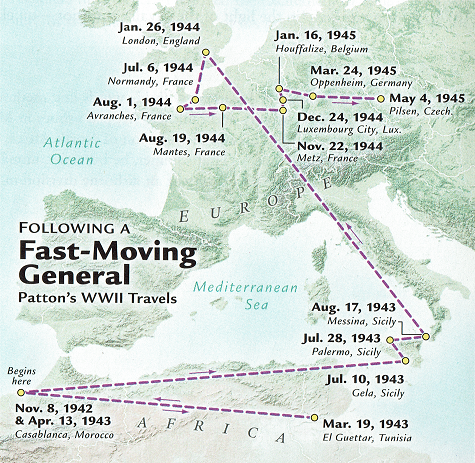

George S. Patton, Jr., first became a national hero as a cavalry officer chasing Mexican revolutionaries with future General of the Armies John J. Pershing in 1916. He sealed his iconic status during World War II, commanding armored troops racing to victory across North Africa, Sicily, France, and Germany from 1942 to 1945.

That didn’t mean everyone was ready to crown him with laurels.

A man of many contradictions, Patton aroused intense emotions in admirers and detractors alike throughout his life. When his French counterpart Major General Paul Girot de Langlade called him “an offensive warrior of high class who seems to have no equal among his compatriots for exploitation warfare,” offensive could have been taken either way.

British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, the only World War II figure whose speeches attracted as much attention as Patton’s, could just as easily have been talking about Patton when he referred to Russia as “a riddle, wrapped in a mystery, inside an enigma.” For example, Patton was a cavalry officer steeped in the romantic traditions of his Confederate ancestors, yet he was the first to make moves to push the US Army into modern, motorized warfare. He was a wealthy aristocrat—his mother’s father was the first mayor of Los Angeles and had a 14,000-acre ranch that later became several California towns, including Pasadena—yet the common men under his command adored him. He was considered an anti-Semite, yet he fought furiously to save Jews from death in the concentration camps of Europe. He hated the Germans he fought against, but aroused controversy after the war when, as military governor of Bavaria, he retained former Nazis in key government positions.

A bigot, Patton was the only major American general to request more black soldiers, the first American general in history to integrate rifle companies, and the first to use black tank units. “I would never have asked for you if you weren’t good,” Patton told the all-black 761st Tank Battalion. “I have nothing but the best in my Army. I don’t care what color you are as long as you go up there and kill those Kraut sons of bitches.”

The contradictions only continued. Deeply religious, he was perhaps the most profane man in the military. Martin Blumenson, editor of The Patton Papers, writes, “He was unpredictable, capricious, at the same time dependable, loyal. He was brutal yet sensitive. He was gregarious and a loner. Enthusiastic and buoyant, he suffered from inner anguish…. Throughout his lifetime he prompted intense devotion as well as instant dislike.”

Many considered Patton to be an oaf (though it’s now assumed he was dyslexic, which could have helped create that perception). But according to military historian Victor Davis Hanson, he was “without question the best-educated, most experienced, and most widely read general in the American army.” Some use the term “genius.” Carlos D’Este titled his Patton biography A Genius for War. “What made Patton so remarkable was his willingness to take risks and to make crucial life-and-death decisions no one else would dare…,” he wrote. “[He had] that intangible, instinctive sense of what must be done in the heat and chaos of battle: in short, that special genius for war that has been granted to only a select few.”

Others are convinced that, far from being a genius, Patton was mentally ill, having suffered permanent brain damage thanks to his reckless lifestyle and long history of injuries. The index to the first volume of The Patton Papers lists almost 40 entries under “sicknesses and accidents.” Over the years, Patton fell off of or was kicked or butted in the head by horses, fractured numerous bones, was shot in battle, and had a gasoline lamp blow up in his face and set his tent on fire. The traffic accident that would finally kill Patton in late 1945 was minor compared to others. “I had my usual yearly accident,” he wrote to his wife, Beatrice, from France in 1917. “The car ran into a closed railroad gate and I carelessly put my head through the front window….”

Patton thrived on publicity, but it brought him low after he slapped two soldiers suffering in Sicily from battle fatigue. Known as Old Blood and Guts—“his guts, our blood,” some GIs said—he was criticized for his viciousness, but also scorned because he raced his troops in swift flanking movements around an enemy, trying to save lives by avoiding bloody frontal assaults.

Patton did have a temper. And he did love war, “but not the death and destruction,” writes Blumenson in The Patton Papers. “The concentration camps and the ruined cities sickened him, and the losses of his soldiers hurt him…. He loved the excitement of war, the responsibility of war, the prerogatives of his position, and, most of all, the opportunity that war presented to use the skill, leadership, and courage required by his profession—in the same way that a surgeon loves his calling but not the disease, illness, and injury he treats.”

“Never take counsel of your fears.”

“Pursue the enemy with the utmost audacity.”

—inscriptions on the Patton statue at West Point

Patton described war as “very simple, direct, and ruthless.” In one of his earliest preserved writings, he outlined his creed: “Attack, push forward, attack again until the end.” Blumenson explains that “the principles he utilized in armored warfare came from the cavalry. He constantly sought surprise, mobility, maneuver…and the relentless pursuit.” According to Hubert Essame, a British major general in WWII and the author of Patton: A Study in Command (1974), Patton worked “in the light of the cavalry tradition—quick decision, speed in execution, calculated audacity; better a good plan violently executed now than a perfect plan next week.”

At the end of July 1944, just before the Third Army became operational with Patton as commander, the general reminded his men, “Forget this goddamn business of worrying about our flanks…. Flanks are something for the enemy to worry about, not us. I don’t want to get any messages saying that, ‘We are holding our position.’ …We’re not interested in holding on to anything except the enemy. We’re going to hold on to him by the nose and we’re going to kick him in the ass.”

Digging a foxhole, Patton believed, was the same as digging a grave. He considered hiding behind fortifications demoralizing; it made a soldier think “the other man must be damned good, or I wouldn’t have to get behind this concrete.” For Patton, speed was essential, a continual forward motion that demoralized the enemy while energizing yourself. This came naturally to the Americans, wrote Australian war correspondent Chester Wilmot, for they “had in their blood a longing for adventure and an instinct for movement, which they inherited from those pioneers who had broken out across the Alleghenies and opened up the Middle West. To the American troops driving across France, distance meant nothing.” Patton felt that troops sitting still, while in contact with the enemy, began brooding and finding their thoughts turning to what could go wrong. “Action, and offensive action at that, alone brings release,” Essame writes. “This, allied with the concept of speed, was the very heart of the Patton approach to battle.”

In the same manner, Patton preached to his Third Army platoons the idea of marching fire, moving forward while everyone shot off a round every two or three steps. “Shooting adds to your self-confidence because you are doing something,” he told them. And the constant noise of the bullets and their ricochet kept the enemy cowering and unable to return fire.

“Truly in war: ‘Men are nothing, a man is everything.’ …The leader must be an actor…. He is unconvincing unless he lives his part.”

—The Secret of Victory (1926), George S. Patton, Jr.

“Drama and Corn. Patton the General is also Patton the Actor. Showmanship is instinctive in him.”

—Time magazine cover story, April 9, 1945

“For Patton, leadership was never simply about making plans and giving orders,” writes Alan Axelrod, author of Patton: A Biography (2006). “It was about transforming oneself into a symbol, a kind of totem or talisman with which the group identified. His message was never we must succeed but always we will succeed.”

Patton worried that his high-pitched speaking voice would not inspire confidence among his troops and would keep him from being the powerful symbol he wanted to be. And annoyed that “for so fierce a warrior, I have a damned mild expression,” he practiced what he called his “war face” before public appearances.

One of the keys to being a successful leader, Patton believed, was to be everywhere, leading by example. To that end, he even went into the skies. Hoping to understand how enemy aircraft would approach a tank squadron, he bought a small plane, took flying lessons, and at age 55 earned his pilot’s license. “Whenever air and armor can work together,” he said, “the results are sure to be excellent. Armor can move fast enough to prevent the enemy having time to deploy off the roads, and so long as he stays on the roads the fighter-bomber is one of his most deadly opponents.”

Coordinating with airpower also meant that Patton would not have to destroy enemy infrastructure, as earlier raiding parties in history had. As he crossed the Rhine, American and British planes blasted German cities. The Third Army was free to concentrate on opposing troops.

“We’re not going to just shoot the sons-of-bitches, we’re going to rip out their living Goddamned guts and use them to grease the treads of our tanks….

“When we get to Berlin, I am going to personally shoot that paper-hanging Goddamned son of a bitch just like I would a snake….”

“The quicker we clean up this Goddamned mess, the quicker we can take a little jaunt against the purple-pissing Japs and clean out their nest, too.”

—excerpts from a Patton speech on the eve of the Normandy invasion, June 5, 1944

Typically, Patton improvised his famous orations. After giving a speech in May 1944, he wrote in his diary, “As in all my talks, I stressed fighting and killing.” It seems fair to say, as Hanson writes, that “Patton never understood [the] rhetorical responsibilities of a public figure.” His words often jarred Americans, whose censors had kept away from them images of death. The first photo of war dead in the immensely popular Life magazine—three dead soldiers on a New Guinea beach—didn’t appear until September 1943, seven months after the shot was taken. Of the 61 war movies made in America during the latter part of 1942, only five showed anyone being killed in combat. Yet there was Patton, during a Memorial Day speech in 1943, saying, “To conquer, we must destroy our enemies…. We must kill devastatingly. The faster and more effectively you kill, the longer you will live to enjoy the priceless fame of conquerors.”

Patton also offended public sensibility by acting on his conviction that “you can’t run an army without profanity…. When I want my men to remember something important, to really make it stick, I give it to them double dirty.” Hanson thinks Patton used his “tirades and crudity” to gear himself up for playing the role of leader. As “efforts to mask the embarrassment of [having] an aesthetic sense,” he writes, Patton’s “often vulgar outbursts about killing, war, sex, and race” put forth “an image of a general who was a warrior always, not a keen student of the arts and sciences.” Patton himself was blunter: “Sometimes I just get carried away with my own eloquence.”

Patton’s best-known speech, delivered in England on the eve of the Normandy invasion, was later sanitized for public consumption and made immortal in that version by George C. Scott as the opening of the movie Patton. Even in its cleaned-up form, it was so strong that Scott worried it would overshadow his performance in the rest of the film. So, director Franklin J. Schaffner reportedly lied and told Scott he wouldn’t place it at the beginning.

Even when his language was clean, Patton himself got into trouble for his frankness. Hanson points out, however, that although the general was criticized for just plain being too blunt—whether about the brutality necessary to defeat the Nazis, the evils of Josef Stalin’s Soviet Union, the need to protect Eastern Europe from Communism, or his hope for a strong, united Germany—“it is difficult to find evidence…that any of Patton’s major political pronouncements were fundamentally wrong.” He also believes, “In every tactical crux of the Normandy campaign, Patton alone offered the correct advice.”

“Almighty and most merciful Father, we humbly beseech Thee, of Thy great goodness, to restrain these immoderate rains with which we have had to contend. Grant us fair weather for battle. Graciously hearken to us as soldiers who call upon Thee that, armed with Thy power, we may advance from victory to victory, and crush the oppression and wickedness of our enemies and establish Thy justice among men and nations. Amen.”

—the Patton Prayer, December 1944

Patton achieved even more notoriety at the end of 1944 when he decided to address a greater audience: God. As James O’Neill, a Catholic priest serving as chief chaplain of the Third Army, tells the story in a 1950 government document, Patton called him in early December and asked, “Do you have a good prayer for weather? We must do something about [the rain that had been falling for months] if we are to win the war.” O’Neill quickly composed a prayer and showed it to Patton, who then asked for 250,000 copies to be printed, so it would be available to every soldier in the Third Army. “I am a strong believer in prayer,” he told the chaplain. “There are three ways that men get what they want: by planning, by working, and by praying.”

The prayer cards, along with Patton’s Christmas greeting to his troops, were passed out during the following week, before the Battle of the Bulge began on December 16. As Patton’s men, now tramping through snow, hurried to the relief of besieged American paratroopers at Bastogne, the heavy cloud and fog cover finally let up enough for hundreds of Allied planes to provide air support. Apparently God was listening.

As O’Neill told it, the next time he saw Patton, in late January 1945, the general smiled and said, “Well, Padre, our prayers worked. I knew they would.” Patton then swung his riding crop and smacked it against the side of the chaplain’s steel helmet. O’Neill explains, “That was his way of saying, ‘Well done.’” Patton would go farther: for writing the seemingly successful prayer, O’Neill received the Bronze Star.

“I am convinced that the best end for an officer is the last bullet of the war.”

—Patton diary entry, August 19, 1944

“…All joking aside I don’t expect ever to be sixty not that it is old but simply that I would prefer to wear out from hard work before then.”

—letter from Patton to his future wife Beatrice, February 21, 1909

Patton survived long enough to make it to V-E Day and, six months later, to age 60. In early December 1945, however, having survived two world wars and a civil war in Mexico, he suffered the last of what he termed his “usual yearly accidents.” One day before he was scheduled to leave Germany for America, while he was on his way to hunt pheasants, his chauffeured 1938 Cadillac staff car rammed into a 2.5-ton truck that suddenly turned into its path. The car was traveling about 30 miles an hour, the truck only 10. Patton’s driver and another passenger in the Cadillac were unhurt, but the general, thrown forward into the roof and the partition behind the driver, suffered severe scalp lacerations and a broken neck. This tank commander who believed in ceaselessly pushing forward was paralyzed, unable to move his arms or legs. He died 13 days later.

General Omar Bradley, who had started as Patton’s subordinate but became his superior (and, eventually, senior military advisor for the movie Patton), thought, “It was better for Patton and his professional reputation that he died when he did. The war was won; there were no more wars left for him to fight…. In time he probably would have become a boring parody of himself—a decrepit, bitter, pitiful figure, unwittingly debasing the legend.” As Axelrod writes, “Dead heroes make the best heroes.”

General George Patton was indeed a hero, even among the best heroes—except to those who thought the contrary. Like most of history’s famous and infamous politicians and generals, he was both revered and reviled. But whether it was friend or foe observing and evaluating him, Patton stayed on course, remaining true to the creed he’d scribbled quickly in his West Point notebook: “Never stop until you have gained the top or a grave.”

Photos, from top:

• In Tunisia in March 1943, Lieutenant General George S. Patton, Jr., keeps an eye on his II Corps as it battles German and Italian forces for control of the El Guettar Valley. Patton had just taken over command of the corps from Major General Lloyd Fredendall, bringing an aggressive leadership style that resulted in victories. NATIONAL ARCHIVES

• Patton was known for racist remarks and attitudes. But when it came to battlefield performance, he valued brave and hard-fighting troops of any skin color or ethnicity. Here, Patton (wearing his famous pearl-handled revolvers) pins the Silver Star on Private Ernest A. Jenkins of New York City, a Quartermaster Corps soldier in Patton’s Third Army. In August 1944, Jenkins and an officer he was driving discovered a German machine-gun nest at Chateaudun, France, and eliminated it, killing three enemy soldiers, wounding others, and capturing 15 Germans hiding in a cave. NATIONAL ARCHIVES

• Patton was a driving force behind development of a substantial modern tank force for the US Army on the eve of American involvement in World War II. Before he was sent overseas to North Africa, Patton (then a major general) commanded the army’s I Armored Corps, leading it in extensive exercises in California’s vast Desert Training Center, which he established. Here, during 1942 maneuvers there, he shoots an azimuth with his compass, standing next to a M3 Stuart tank. NATIONAL ARCHIVES

• Patton’s journey through World War II led him from Tunisia all the way to Czechoslovakia. DREAMLINE CARTOGRAPHY/DAVID DEIS

• With the war won and over, Patton, a master horseman, enjoys a chance to ride Favory Africa, from the world-renowned Spanish Riding School of Vienna, Austria. It’s August 22, 1945, at St. Martin, Austria, where the US Army has returned the horse, a bit of living war plunder. Nazi German Chancellor Adolf Hitler had seized the horse as a future gift for Emperor Hirohito of Japan. NATIONAL ARCHIVES

Links to More Information

GEORGE PATTON AND THE CAMERA

See more images of the much-photographed General George S. Patton, Jr.

PATTON’S GHOST ARMY

Find out about the secret project handed to Patton before he publicly took command of the Third Army.

FOLLOW US »