A rubber raft splashed ashore in the dark at Bar Harbor, Maine, on the night of November 29, 1944. Clearly, the men in the raft were up to something…

By Richard Sassaman

with illustrations by Paul Whitman

It was 20 degrees and snowing late in November 1944 near the resort town of Bar Harbor, Maine, some 4,000 miles from Nazi Germany. Two men made their way along the beach, slipping through snow and tripping over exposed tree roots. Erich Gimpel and William Colepaugh would have looked like any other men but for the heavy suitcases they lugged and their light topcoats, which were no match for the northeastern winter. As they moved toward the cover of the thick coastal woods, two other men stood by, dressed in Nazi navy uniforms. These two were "possibly the first enemy dressed in a military uniform to set foot on continental U.S. soil since the Mexican War in the 1840s," writes former US intelligence officer Richard Gay, coauthor of the book They Came To Destroy America (2003).

It was 20 degrees and snowing late in November 1944 near the resort town of Bar Harbor, Maine, some 4,000 miles from Nazi Germany. Two men made their way along the beach, slipping through snow and tripping over exposed tree roots. Erich Gimpel and William Colepaugh would have looked like any other men but for the heavy suitcases they lugged and their light topcoats, which were no match for the northeastern winter. As they moved toward the cover of the thick coastal woods, two other men stood by, dressed in Nazi navy uniforms. These two were "possibly the first enemy dressed in a military uniform to set foot on continental U.S. soil since the Mexican War in the 1840s," writes former US intelligence officer Richard Gay, coauthor of the book They Came To Destroy America (2003).

The uniformed Nazis offered a parting "Heil Hitler" salute. With that, they climbed into a rubber raft and rowed back to a U-boat, where they may have boasted about having "invaded" the United States. The submarine that had brought the Nazis to the rugged coast of Maine had been at the entrance to Frenchman Bay for eight days. On the ocean floor, as fishing boats passed overhead, the 56 men aboard waited for the right opportunity for the two plainclothes spies to head for land. Operation Magpie, the final attempt by Nazi spies to infiltrate America, had begun. (See sidebar about a womanizing Nazi spy who had headed for the coast of Maine six weeks earlier.)

Erich Gimpel—the most accomplished German spy to make it into the United States, was a very unlikely agent. Born on March 25, 1910, Gimpel began his espionage career in the mid-1930s in Peru, where he was working as a radio engineer for mining companies. Like a character in a Graham Greene spy novel, he was told by the German government to track ship movements in the area and send his information to a contact in Chile. "In Lima I never missed a party," he later wrote, describing the whole thing as somewhat of a lark. "We were fighting our war in dinner jackets and with cocktail glasses in our hands."

Erich Gimpel—the most accomplished German spy to make it into the United States, was a very unlikely agent. Born on March 25, 1910, Gimpel began his espionage career in the mid-1930s in Peru, where he was working as a radio engineer for mining companies. Like a character in a Graham Greene spy novel, he was told by the German government to track ship movements in the area and send his information to a contact in Chile. "In Lima I never missed a party," he later wrote, describing the whole thing as somewhat of a lark. "We were fighting our war in dinner jackets and with cocktail glasses in our hands."

When America entered World War II, Gimpel was deported from Peru with other Germans and sent to Texas where he spent seven weeks in an internment camp. On his arrival back in Germany, Gimpel was welcomed by a stranger who gave him money and identity and ration cards, and told him to report to an address in Berlin. "I knew this was the headquarters of the German Secret Service," he wrote. "The amateur was about to become an expert."

William Colepaugh was an even more unlikely Nazi spy. For starters, he was an American, born in Connecticut (exactly eight years after Gimpel) and educated at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. After the war began, his pro-German attitudes got him into trouble with his Selective Service Board and the FBI. Colepaugh eventually took a kitchen job on a Swedish ship in early 1944 just to get across the Atlantic. He abandoned ship in Lisbon, the capital of Portugal, and presented himself to the German consul. Unable to speak German, he announced in English that he wanted to help Germany win the war. The fact that his mother was German did not keep the Nazi diplomat from wondering whether this American was really an Allied agent trying to get inside the Third Reich.

William Colepaugh was an even more unlikely Nazi spy. For starters, he was an American, born in Connecticut (exactly eight years after Gimpel) and educated at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. After the war began, his pro-German attitudes got him into trouble with his Selective Service Board and the FBI. Colepaugh eventually took a kitchen job on a Swedish ship in early 1944 just to get across the Atlantic. He abandoned ship in Lisbon, the capital of Portugal, and presented himself to the German consul. Unable to speak German, he announced in English that he wanted to help Germany win the war. The fact that his mother was German did not keep the Nazi diplomat from wondering whether this American was really an Allied agent trying to get inside the Third Reich.

From Lisbon, Colepaugh traveled through France to Berlin, where German authorities watched him closely for three months. Finally, he was interviewed by SS Major Otto Skorzeny, Hitler’s favorite commando. In June 1944, Skorzeny sent him to an SS training school where he himself taught, in the German-occupied Netherlands. There, Colepaugh met Erich Gimpel, who considered the "young, well-fed, and contented" American not a problem, but a potential solution.

Gimpel had been asked to infiltrate America to uncover details about the United States’ program to develop an atom bomb—the Manhattan Project. He had ~reed on one condition. To survive as a spy in the United States, Gimpel had concluded, he would need to take along "a proper American. He must know the latest dance steps and the latest popular songs. He must know everything about baseball and have all the Hollywood gossip at his fingertips." That said, Gimpel had to wonder where he would find "an American who was prepared to work against his own country and who at the same time was courageous, sensible, and trustworthy."

Colepaugh appeared to be just what Gimpel needed. Late in September 1944, the two men boarded the 252-foot, IXC/40-class U-1230 in Kiel, Germany, bound for Maine. Ordinarily, the vessel carried a full crew of 56, but two of the regulars were left behind to make room for the spies. Their agents’ mission and identities were kept secret even from the young crewmen and their commander, with Gimpel posing as a chief engineer and Colepaugh as a war correspondent. The crew soon figured out that something was amiss, though: how could a man who didn’t speak German be a German reporter?

The sub entered the open ocean on October 6. It was a dangerous time for a U-boat to cross the Atlantic; in fact, the U-1230’s sister ship U-1229 was headed for Maine about six weeks earlier when she was sunk in the North Atlantic by Navy planes from the aircraft carrier USS Bogue.

To help make their way in the United States, Gimpel and Colepaugh carried $60,000 in small bills (the equivalent of $656,000 today). Colepaugh had convinced his superiors that a person could hardly get by in America on less than $15,000 a year—at a time when the average family income was about $2,250. The money was supposed to keep the two spies in the United States through 1946. Along with the cash, the men had also been given 99 small diamonds to sell if the US currency had changed by the time they arrived or if they eventually needed additional funds. Checking on the holdings one day as the submarine neared Maine, Gimpel was shocked to find the American money bundled in wrappers printed "Deutsche Reichsbank." He quickly disposed of that evidence.

U-1230 had been equipped for a six-month patrol, and ‘carried 14 torpedoes. Nevertheless, she was under orders not to attract attention until her primary mission of delivering Gimpel and Colepaugh to the United States had been accomplished. After five weeks of a largely uneventful voyage, the submarine reached the coast of Newfoundland and continued south from there down the Maine coast. Along the way, the sub’s transformer and depth-finding equipment was damaged by condensation caused by weeks of traveling underwater. The equipment had to be repaired on the surface, so the vessel was taken up under the cover of night. The repairs succeeded, and the surface activity went unnoticed.

Finally, on November 29, after almost two months at sea, the sub made its way a dozen miles up Frenchman Bay between the islands just off Bar Harbor. (About 31 feet high, the sub had a draft of just over 15 feet.) Shortly before 11 p.m., near Sunset Ledge on the western side of Hancock Point, it came to a stop a few hundred yards off shore, with only its conning tower showing above the water.

A rubber raft was brought up and inflated by a line connected to a silent air compressor. The original plan called for the two spies to row themselves ashore, at which point the raft would be pulled back to the sub on a light tether. The line broke, however, making it necessary for the two uniformed sailors to come along—and earn a moment of glory on the US mainland.

Even today, 60 years later, you’ll find this remote area of the Maine coast deserted at midnight. In 1944, "there probably were less than a dozen families" near where the spies landed, says Lois Johnson of the Hancock Historical Society. The Hancock Town Report for 1944 lists 13 births, 12 deaths, and two marriages. Census figures show that the population grew from 755 to only 770 between 1920 to 1950.

Hancock was a place with few people around to notice anything that might happen, but also a place where strangers stood out. Two people did happen to drive by as Gimpel and Colepaugh were walking along the road at that late hour. Both of them spotted the men, but neither stopped: Hancock was also a place where people minded their own business.

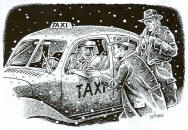

After the men reached US Route 1, a third car passed them, and it did stop. Miraculously, it was a taxicab from Ellsworth, the small town eight miles to the west. Colepaugh did all the talking, explaining that their car had slid into a ditch in the storm and they needed a ride to the train station in Bangor, 35 miles away. So followed a $6 cab ride and a 2 A.M. train to Portland. Stopping there for a bite to eat, Gimpel stammered when a short-order cook asked him what kind of bread he preferred with his ham and eggs. To him, bread was bread, and "the fact that in America people ate five different kinds" was surprising, he wrote.

The spies boarded a train to Boston at 7 a.m. That afternoon, Gimpel went into a store in town to buy a tie, and the salesman recognized the cloth and cut of his trench coat as not being American. "As a matter of fact," Gimpel managed to reply, "I bought it in Spain." He decided never to wear that coat again. Gimpel and Colepaugh spent the night in a hotel, sleeping in their American clothes to try and make them look less new. They left the next day, completing their journey with a train ride to Grand Central Station in New York City. In less than 40 hours the intruders had gone from the middle of nowhere in Maine to downtown Manhattan. It was a remarkably efficient journey.

The pair checked into a hotel on 33rd Street. They spent most of the next week looking for a place not constructed of steel, because steel hindered radio transmissions. They found an apartment on Beekman Place for $150 a month and paid two months’ rent in advance.

Things had gone well so far for the two Nazi spies on American soil, but over the next few weeks, their luck began to wear out. Two days after their arrival in New York, U-l230, still lingering about the coast, sank the 5,458-ton Canadian freighter Cornwallis, which was carrying sugar and molasses from Barbados to St. John, New Brunswick. Alarmed by the possibility that this U-boat could have dropped off enemy agents, the Boston FBI office sent men north to Maine. The agents soon located 29-year-old Mary Forni and her next-door neighbor, 17-year-old Harvard Hodgkins, the two Hancock residents who had driven past the spies walking in the snow. Forni, the wife of the Hancock tax collector, had been out late playing cards with friends; Hodgkins, son of the town’s deputy sheriff and a Boy Scout and assistant scout leader, had been at a dance. They both described to the agents what they had seen.

Much has been made of the Nazis getting away with walking through the Maine woods in a late November snowstorm dressed in light topcoats, advertising themselves as outsiders. But such hindsight misses the point, says Richard Gay. "The truth is," he told an interviewer, "their cover was perfect, and it worked without a hitch." As far as any witnesses knew, the spies "were visitors from the city whose car had broken down."

What really broke down on the spy mission was William Colepaugh. Deciding that espionage was not for him, he took off on December 21 with both suitcases, including all the cash. Gimpel returned to the apartment to find everything gone and figured out that his partner must have headed back to Grand Central Station. There, Gimpel found the suitcases in the baggage room and, after some anxious moments, managed to recover them, even though he did not have the claim checks.

Gimpel had proven resourceful in responding to every mishap so far, but he had no answer for what happened two days later: Colepaugh, meeting with an old school friend, confessed that he was a spy. The friend at first thought Colepaugh was joking, but after he realized the story was true, he called the FBI. A manhunt immediately centered on Manhattan, and Gimpel was captured on December 30.

In early February 1945, Gimpel and Colepaugh were tried by a military court at Fort Jay on Governors Island, New York. They were convicted and, on Valentine’s Day, sentenced to death by hanging. Before their sentence was carried out, however, President Franklin D. Roosevelt died, and all federal executions were suspended for four weeks. By the time that month was up, the war had ended in Europe, and on June 23, new president Harry S. Truman announced that he was commuting the two sentences to life in prison—Gimpel’s because the United States and Germany were no longer at war, and Colepaugh’s because he had given himself up and provided the FBI with the information needed to arrest Gimpel. A statement from the War Department, reported in The New York Times, ended with the confident conclusion "The mission of the spies in this country was a complete failure."

Colepaugh served 17 years in prison, then moved to the Philadelphia area. He reportedly lives in a rest home in Florida today. Gimpel served 10 years at Leavenworth, Alcatraz, and Atlanta before he was released and deported to Germany in 1955. He later moved to Brazil, where he celebrated his 94th birthday in 2004. In 1991 and again in 1993 he visited Chicago as the honored guest of the Sharkhunters, a group of some 7,000 U-boat enthusiasts from 70 countries.

Gimpel was not the only Nazi from this spy mission to return to America. Horst Haslau, the radioman aboard the U-1230 and one of the vessel’s youngest crewmen, got a job in the United States. In 1984, he was working for RCA in Indianapolis, Indiana, and visited the Hancock area. The local newspaper published photos of America’s one-time enemy wearing a John Deere cap and sitting in the Ellsworth Holiday Inn, holding a bottle of beer. The brand was Beck’s, the same German beer that was stocked on U-1230, Haslau said. Three weeks after the sub dropped off Gimpel and Colepaugh in Maine, he recalled, each crewmember received one bottle for Christmas.

Forni continued to live in the Hancock area and was one of the guests of honor at a June 2005 party to celebrate the 90th birthday of some local residents. Sixty years earlier, she had been honored at another local party; shortly after the spy incident, her friends organized an event to honor her for her role in providing information that helped capture Gimpel and Colepaugh and presented her with a $100 war bond.

Americans ate up the story of Hodgkins, the Hancock Boy Scout. The New York Journal-American sponsored the high school senior’s first ride in an airplane, bringing him and his family to New York for a week in January 1945, where he was given a key to the city. He saw the Statue of Liberty, Radio City Music Hall, and some Broadway shows, and met Governor Thomas Dewey, boxing champion Joe Louis, and Babe Ruth. After he graduated from Ellsworth High School, Hodgkins received a full scholarship to the Maine Maritime Academy for his anti-spy efforts. He died in May 1984.

Given what we know about Operation Magpie, Gimpel and Colepaugh were probably no great threat to America’s security. They had little skill and experience to aid them in circumventing the huge obstacles that remained in their path. In the end, the chief result of their mission was to turn a couple of ordinary Americans in Hancock, Maine, into heroes. Gimpel and Colepaugh were left with the claim to the fairly weightless title Last Nazi Spies in America.

Bottom illustration: During a layover in Boston, Gimpel visited a clothier, where an alert salesman noticed his suit wasn’t made in the United States. Gimpel talked himself out of the jam.

Photos: Adolf Hitler’s favorite commando, SS Major Otto Skorzeny (left), personally selected Gimpel (right) to attend the SS training center in the Netherlands where he taught.

Copyright 310 Publishing, LLC. All rights reserved.

FOLLOW US »