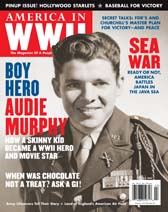

Rejected twice for war service, this scrawny Texas farm boy became America’s most decorated WWII hero–and a movie star.

By Tom Huntington

A search party struggled through thick woods on Virginia’s Brush Mountain. Atop the 3,065-foot peak about 12 miles from Roanoke, the searchers came upon the plane wreckage a helicopter crew had spotted earlier. They found three bodies in the mangled fuselage and three others in the scattered debris. Among the dead was 46-year-old Audie Murphy, the most decorated veteran in US history.

Murphy, who had been flying to Virginia to check out an investment opportunity, had earned 21 medals in World War II, including the Congressional Medal of Honor. After the war he had appeared in many movies, some good, most mediocre. By the time the plane crashed on May 23, 1971, he seemed to be a man from another time. News of his death shared the front page of the New York Times with accounts of Memorial Day protests against the Vietnam War.

Murphy was buried with full military honors at Arlington National Cemetery as his wife and two sons looked on. Army Chief of Staff William Westmoreland attended the ceremony. President Richard Nixon’s White House issued the statement that Murphy had “not only won the admiration of millions for his own brave exploits, he also came to epitomize the gallantry in action of America’s fighting men.”

Sadly, Murphy just as thoroughly epitomized the dark corollary to “gallantry in action,” the psychological toll that war can inflict on even the most courageous warriors. Although he was wounded three times in battle, his deepest scars weren’t physical. He suffered from terrible nightmares, slept with the lights on and a gun under his pillow, gambled heavily, and found little to interest him after his high-stakes existence on the front lines. “Seems as though nothing can get me excited any more—you know, enthused?” he told director John Huston after being cast in The Red Badge of Courage. “Before the war, I’d get excited and enthused about a lot of things, but not any more.”

Sadly, Murphy just as thoroughly epitomized the dark corollary to “gallantry in action,” the psychological toll that war can inflict on even the most courageous warriors. Although he was wounded three times in battle, his deepest scars weren’t physical. He suffered from terrible nightmares, slept with the lights on and a gun under his pillow, gambled heavily, and found little to interest him after his high-stakes existence on the front lines. “Seems as though nothing can get me excited any more—you know, enthused?” he told director John Huston after being cast in The Red Badge of Courage. “Before the war, I’d get excited and enthused about a lot of things, but not any more.”

Born on June 20, 1924, near the Texas town of Kingston, Murphy was one of nine surviving children of parents who eked out a living from the land. “We were share-crop farmers,” he wrote. “And to say that the family was poor would be an understatement. Poverty dogged our every step.” When Murphy was 16, his father left. “He simply walked out of our lives, and we never heard from him again,” Murphy wrote. His mother died the next year, and Murphy took her death hard. The family had to break up, and Murphy’s three youngest siblings were sent to an orphanage.

The coming of war with the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, seemed to promise a way out of a bad situation, although Murphy—short, freckle-faced, and slight—seemed an unlikely warrior. The marines wouldn’t take him. Neither would the paratroopers. When he finally managed to enlist in the infantry, he was 18, but he looked younger. His sergeant at training camp called him Baby, and Murphy passed out during his first close-order drill. Commanders tried to keep him from combat, suggesting they could get him posted as a clerk or a baker. But he wanted to fight.

The chance finally came when Murphy’s Company B of the 15th Regiment, 3rd Division, landed in Italy. He killed his first enemy soldiers in Sicily: two Italian officers who tried to gallop away on horseback. “I feel no qualms; no pride; no remorse,” he said in To Hell And Back, the 1949 autobiography he co-wrote with journalist and friend David McClure. “There is only a weary indifference that will follow me throughout the war.” Even at this early stage in his combat career, he was learning how to suppress his emotions.

From Sicily, Murphy’s company moved to the Italian mainland. A bout of malaria kept him from participating in the initial landings at Anzio, but he saw action enough. German resistance stiffened after the landings, and the Allied soldiers endured a miserable stalemate. One night, while under fire, Murphy crept up to a damaged German tank and put it permanently out of commission. The attack earned him his first medal, a Bronze Star.

Such a daring attack became typical of Murphy. He was a crack shot, his battlefield instincts were razor-sharp, and he seemed to be fearless. “If I discovered one valuable thing during my early combat days, it was audacity, which is often mistaken for courage or foolishness,” he said. “It is neither. Audacity is a tactical weapon. Nine times out of ten it will throw the enemy off balance and confuse him.”

Audacity or not, fear never completely disappeared. “In the heat of battle it may go away,” Murphy wrote. “Sometimes it vanishes in a blind, red rage that comes when you see a friend fall. Then again you get so tired that you become indifferent. But when you are moving into combat, why try fooling yourself? Fear is right there beside you.”

Company B left Italy on August 12, 1944, to fight in Operation Dragoon, the Allied invasion of Southern France. The Americans swarmed ashore almost unopposed. Murphy, now a sergeant, was heading inland with Company B when a German machine gun on a ridge above a vineyard pinned them down. Private Lattie Tipton, a lanky 33-year-old Tennessean who had become Murphy’s closest friend and a father figure of sorts, followed Murphy forward to take on the Germans. Murphy urged him to head back and get a wounded ear treated, but Tipton refused. “Come on Murphy,” he said, “let’s move up. They can kill us, but they can’t eat us. It’s against the law.” Minutes later Tipton was dead. The Germans waved a white flag, and Tipton, though an experienced infantryman, made the mistake of standing up. German machine guns treacherously shot him right back down.

Company B left Italy on August 12, 1944, to fight in Operation Dragoon, the Allied invasion of Southern France. The Americans swarmed ashore almost unopposed. Murphy, now a sergeant, was heading inland with Company B when a German machine gun on a ridge above a vineyard pinned them down. Private Lattie Tipton, a lanky 33-year-old Tennessean who had become Murphy’s closest friend and a father figure of sorts, followed Murphy forward to take on the Germans. Murphy urged him to head back and get a wounded ear treated, but Tipton refused. “Come on Murphy,” he said, “let’s move up. They can kill us, but they can’t eat us. It’s against the law.” Minutes later Tipton was dead. The Germans waved a white flag, and Tipton, though an experienced infantryman, made the mistake of standing up. German machine guns treacherously shot him right back down.

Tipton’s death swept Murphy into a blur of fury. “I remember the experience as I do a nightmare,” he wrote. “A demon seems to have entered my body. My brain is coldly alert and logical. I do not think of the danger to myself. My whole being is concentrated on killing. Later the men pinned down in the vineyard tell me that I shout pleas and curses at them, because they do not come up and join me.” Using a captured German machine gun, Murphy methodically mowed down the Germans who had killed his friend. “As the lacerated bodies flop and squirm, I rake them again,” Murphy wrote; “and I do not stop firing while there is a quiver of life left in them.” Murphy won the Distinguished Service Cross for his actions that day. He gave the medal to Tipton’s daughter.

To this point in the war, Murphy had somehow survived physically unscathed. He received his first wound as the Americans pushed northward through France, the German army retreating before them into the Vosges Mountains. During one fight, a mortar shell struck near him, killing two soldiers and knocking him unconscious. The blast shattered the stock of his lucky carbine (which he wired back together), but his own injuries were only minor.

Murphy’s battlefield prowess did not go unnoticed, and despite his protests that he wanted to remain among the rank and file, he was commissioned a second lieutenant on October 14, 1944. Less than two weeks later, as frosty weather hinted at the bitter winter to come, a hidden German rifleman shot him in the hip. Even wounded and on the ground, Murphy managed to kill the sniper before the sniper could finish him off. But his wound soon became infected, and surgeons had to remove a large chunk of flesh from his hip. Murphy rejoined Company B three months later, just in time for one of the unit’s most difficult actions: defeating the German troops in the Colmar Pocket, a bulging salient that extended into France on the west bank of the Rhine River.

Murphy’s battlefield prowess did not go unnoticed, and despite his protests that he wanted to remain among the rank and file, he was commissioned a second lieutenant on October 14, 1944. Less than two weeks later, as frosty weather hinted at the bitter winter to come, a hidden German rifleman shot him in the hip. Even wounded and on the ground, Murphy managed to kill the sniper before the sniper could finish him off. But his wound soon became infected, and surgeons had to remove a large chunk of flesh from his hip. Murphy rejoined Company B three months later, just in time for one of the unit’s most difficult actions: defeating the German troops in the Colmar Pocket, a bulging salient that extended into France on the west bank of the Rhine River.

On January 26, Murphy and Company B found themselves on the outskirts of woods facing the German village of Holtzwihr. The day dawned miserably cold and uncomfortable as the small American force waited tensely for an attack. Finally, six German tanks supported by infantry began moving toward them from the village and quickly put two American tank destroyers near Murphy’s company out of action. Murphy sent his men back, but he stayed put with his field telephone. He was only 20 years old, and it did not look like he would live to see 21.

With his phone, Murphy called in artillery fire on the advancing German infantry. German tanks were approaching on his sides, but Murphy climbed onto a burning tank destroyer—which could have exploded at any second—and began firing its .50-caliber machine gun. He killed dozens of German soldiers, forcing the tanks to fall back due to lack of infantry protection. One German squad sneaking up on Murphy’s right got as close as 10 yards from him before he detected the threat. He shot the whole squad down. Somewhere along the way, Murphy got hit in the leg, but he kept fighting until he ran out of ammunition. Having killed about 50 Germans, he returned to his company, where he refused medical help and instead rallied his men to make a counterattack. The Germans were forced to retreat.

Later, Murphy heard that the enemy had stayed away from his burning tank destroyer because it looked ready to blow up. “I do not know about that,” he answered in his memoir, putting himself back into the scene. “I am conscious only that the smoke and the turret afford a good screen, and that, for the first time in three days, my feet are warm.”

Murphy’s heroics at Holtzwihr earned him the Congressional Medal of Honor, the nation’s highest military award. The citation read, “Lt. Murphy’s indomitable courage and his refusal to give an inch of ground saved his company from possible encirclement and destruction, and enabled it to hold the woods which had been the enemy’s objective.” When the army found out Murphy was going to receive the medal, it pulled him off the front lines; too many of these medals had ended up being awarded posthumously. Still, Murphy found a way into combat. On one occasion he went in to rescue his company when it was pinned down by German fire along the Siegfried Line in western Germany.

In June 1945, Murphy finally returned. He was a national hero. Life magazine put him on its cover, identifying him simply as “America’s Most Decorated Soldier.” The story inside told of his return to Farmville, Texas. One photograph showed him with his “special girl,” 19-year-old Mary Lee. “Audie hopes she is his own girl,” the caption read, “but he isn’t quite sure yet because he usually blushes when he gets within ten feet of any girl.” The Murphy Life portrayed could hardly have been more different from the Murphy that McClure came to know. While the two men worked together on To Hell And Back, Murphy told McClure about an Italian family in Rome that had invited him to dinner one day. Murphy said that before dinner he seduced the two daughters, and afterward, for good measure, he seduced the mother. “Audie seduced more girls than any man I ever knew with the possible exception of Errol Flynn,” McClure said. “He might even have topped Flynn.”

The Life story opened an unexpected door for Murphy. Actor James Cagney saw it and invited the young veteran to Hollywood. “All I saw him as was a typical fighting Irishman,” Cagney said. “Perhaps I imagined there was a little bit of me in Audie.” Cagney put Murphy up for a time in his Hollywood home and provided him with acting classes, but after two years, the country’s most decorated soldier was broke and living above a gymnasium.

It was around this time that McClure met Murphy. McClure was a fellow Texan and ex-army man, now working as an assistant to Hollywood gossip columnist Hedda Hopper. He heard of Murphy’s plight and began to champion him. The two men became friends and started working on To Hell And Back, with McClure prodding the reluctant Murphy to provide material he could use in the book. “Audie had been burned out by the war,” McClure said later. “He reacted intensely to the death of his friends in combat. I supposed in order to keep from going insane he buried his emotions so deeply that getting them back was difficult if not impossible.” But McClure persevered, making up the material that Murphy couldn’t—or wouldn’t—supply, and the book came out in 1949 to favorable reviews.

McClure also used his Hollywood connections to help Murphy get movie roles. The first was in 1949’s Bad Boy. Murphy remained clear-eyed about his abilities. “You must remember I’m working under a handicap,” Murphy told the director in his self-deprecating way. “No talent.”

For the most part, Murphy acted in Western B-movies. One exception was The Red Badge of Courage, director John Huston’s 1951 adaptation of Stephen Crane’s story about a Civil War soldier who flees from battle. MGM didn’t want Murphy, but Huston fought for him, realizing he had the right qualities for the role. “They just don’t see Audie the way I do,” he said. “This little, gentle-eyed creature. Why, in the war he’d literally go out of his way to find Germans to kill. He’s a gentle little killer.”

There was another famous WWII veteran in Red Badge: Bill Mauldin, whose cartoons about the inanities of army life entertained GIs in the army publication Stars and Stripes. He had some sharp recollections of Murphy. “He was a scrappy little sonofabitch,” Mauldin said. “He would get into bare-knuckle fistfights just for fun with stuntmen. He was five foot four and he’d beat these guys up. They were tangling with a wildcat. That’s why Huston really liked him.”

Murphy delivered a fine low-key performance, but the movie never found an audience. After two disastrous previews, MGM cut the running time to less than 70 minutes and the film flopped. Red Badge was probably Murphy’s best shot at stardom; now he slowly slipped back into the grind of forgettable B-movies. “I’m grateful to the movie business,” he said. “The only trouble is the type-casting. You make a success in Westerns, they milk it dry—until you are dry. That’s why Hollywood has just about dried up for somebody like me.” Murphy categorized himself as “a middle-sized failure.”

Murphy had one undeniable film success: playing himself in Universal’s 1955 adaptation of To Hell And Back. He re-created his combat experiences—even though they were layered over with Hollywood gloss—with an understated dignity that helped lift the movie above its otherwise pedestrian treatment of the war. The movie remained Universal’s biggest moneymaker until Jaws in 1975.

On the personal front, Murphy’s life maintained a slow downward slide. He married starlet Wanda Hendrix in 1949, but the marriage lasted only 15 months. Four days after his divorce, in 1951, he married Pamela Archer. That marriage, too, was strained. Murphy was a haunted man, tortured by insomnia, his nights interrupted by a recurring nightmare in which an army of faceless men attacked him on a hill. Murphy fought back in the dream with his trusty M-1 Garand rifle, but pieces of the gun kept flying off until he had only the trigger guard left.

Plagued by nightmares and sounds he thought he heard, Murphy began sleeping in a bedroom made up in his converted garage, with the lights on and with a pistol under his pillow. He tried using tranquilizers but got addicted to them, finally throwing away the pills and locking himself in a hotel room until the withdrawal symptoms ceased. He acted in more and more forgettable movies, invested in real estate, bred horses, and gambled. “I didn’t care if I won or lost,” he said; “it was as if I wanted to destroy everything I had built up.” In 1968 he went bankrupt. Two years later, he was in the headlines again, when he and a friend were charged with beating up a dog trainer. In every news story, he was invariably identified as “America’s most decorated soldier.”

The experiences that had earned Murphy his decorations had taken their toll. Today, his symptoms would be diagnosed as post-traumatic stress disorder, but that term didn’t exist during his lifetime. He had emerged from the crucible of war, but he had not emerged unchanged. He had seen men die—ripped apart by machine guns, run over by tanks, obliterated by mortar fire. He had killed many men himself, supposedly accounting for 240 Germans single-handedly. “To become an executioner, somebody cold and analytical, to be trained to kill, and then to come back into civilian life and be alone in the crowd—it takes an awful long time to get over it,” he told journalist Thomas Morgan in 1967. “Fear and depression come over you.”

When Morgan visited Murphy at his house in California to interview him, he saw a small glass display box with some of his medals inside. The display was in disarray. The Medal of Honor looked “tacky,” Morgan noted, while the first of Murphy’s three Purple Hearts had fallen and lay face down at the bottom of the case. Like Murphy himself, the medals were ignored, forgotten. At the time of Morgan’s visit, Murphy, America’s most decorated soldier, had four more years to live. But part of him had already died, long before his airplane crashed into the top of Brush Mountain.

Copyright 310 Publishing, LLC. All rights reserved.

FOLLOW US »